|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Climate

Impacts in the Northwest Climate

Impacts in the Northwest

Overview

The Northwest is best known for its vast Pacific coastline

and rainy weather. The region is home to the Cascade

Mountain Range that runs north-south through Washington and

Oregon, resulting in large climatic differences on the

western and eastern sides of the range. West of the

mountains, year-round temperatures are mild, winters are

wet, and summers are dry. East of the mountains, it is

typically sunnier and drier throughout the year, winters are

colder, and summers can be significantly hotter.

Over the last century, the average annual temperature in the

Northwest has risen by about 1.3°F. Temperatures are

projected to increase by approximately 3°F to 10°F by the

end of the century, with the largest increases expected in

the summer. Precipitation in the region has seen a decline

in both the amount of total snowfall and the proportion of

precipitation falling as snow. Declines in snowpack and

streamflows have been observed in the Cascades in recent

decades. In Washington state, record low snowpack values

were measured in April 2015 and in seventy-four percent of

long-term monitoring stations. Changes in average annual

precipitation in the Northwest are likely to vary over the

century. Summer precipitation is projected to decline by as

much as 30%, with less frequent but heavier downpours. |

|

Impacts

on Water Resources Impacts

on Water Resources

A reliable supply of water is crucial for energy production,

agriculture, and ecosystems. Much of the Northwest's water

is stored naturally in winter snowpack in the mountains. The

snowpack melts and replenishes streams and rivers in the

late spring and summer, when there is very little rainfall.

Climate change threatens this natural storage by changing

the timing of snowmelt and the amount of water available in

streams and rivers (streamflow) throughout the year. Warmer

springs contribute to earlier melting of the snowpack,

higher streamflows in late winter and early spring, and

lower flows in summer. Spring snowmelt is projected to occur

three to four weeks earlier by mid-century and summer

streamflows are likely to decline. In the Cascade Mountains,

measurements of snowpack taken on April 1 (when snowpack is

usually at its peak) have decreased by about 20% since the

1950s.

Picture - Natural

surface water availability during late summer is projected

to decline across most of the Northwest. This map shows

expected changes in local runoff (shading) and streamflow

(colored circles) for the 2040s (compared to the period 1915

to 2006), assuming that heat-trapping greenhouse gases will

be reduced in the future. Source: USGCRP 2014

Climate change can also lead to changes in the type of

precipitation. Warmer winters cause more precipitation to

fall as rain instead of snow, particularly at lower

elevations. This reduces soil moisture, snow accumulation,

and the amount of water available from snowmelt. Further,

increased flood risks around rivers that receive waters from

both winter rains and peak runoff in late spring are

expected.

Changing streamflows are likely to strain water management

and worsen existing competition for water. Competing demands

for water currently include hydropower, agricultural

irrigation, municipal and industrial uses, and protection of

ecosystems and threatened or endangered species. Increasing

temperatures and populations could deepen demand and further

stress urban water supplies that are already at risk of

diminishing because of climate change.

Forty percent of the nation's hydropower is generated in the

Northwest. Lower streamflows will likely reduce

hydroelectric supply and could lead to large economic losses

in the region. Reduced streamflows combined with rising

temperatures and a growing population are raising concerns

about the ability to meet increased air conditioning and

other electricity demands.

For more information on climate change impacts, please visit

the Water Resources Impacts or the Energy Impacts pages. |

Impacts

on Coastal Resources Impacts

on Coastal Resources

Climate change is damaging the Northwest coastline.

Projections indicate an increase of 1 to 4 feet of global

sea level rise by the end of the century, which may have

implications for the 140,000 acres of the region that lie

within 3.3 feet of high tide. Sea level rise and storm surge

pose a risk to people, infrastructure, and ecosystems,

especially in low lying areas, which include Puget Sound.

Warming waters and ocean acidification threaten economically

important marine species and coastal ecosystems.

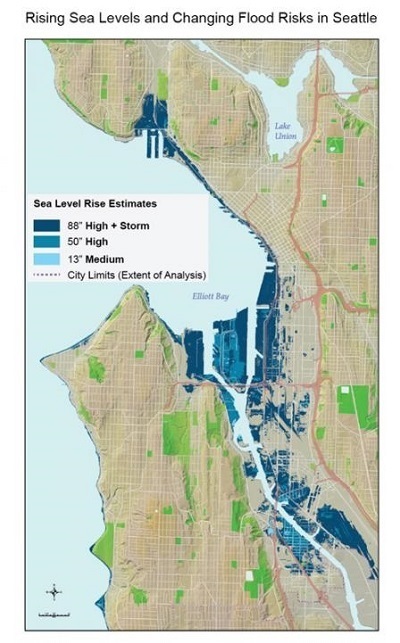

Picture - Many areas

of Seattle are projected to fall below sea level during high

tide by the end of the century. Shaded blue areas depict

three levels of sea level rise, assuming no adaptation. The

high (50 inches) and medium (13 inches) estimates are within

the range of current projections, while the highest level

(88 inches) includes the effect of storm surge. Source:

USGCRP 2014

Flooding, seawater inundation, and erosion are expected to

threaten coastal infrastructure, including properties,

highways, railways, wastewater treatment plants, stormwater

outfalls, and ferry terminals. Coastal wetlands, tidal

flats, and beaches are likely to erode or be lost as a

result of seawater inundation, which heightens the

vulnerability of coastal infrastructure to coastal storms.

Some coastal habitats may disappear if organisms are unable

to migrate inland because of topography or human

infrastructure. This is expected to affect shorebirds and

small forage fish, among other species. Warmer waters in

regional estuaries, including Puget Sound, may contribute to

an increase in harmful algal blooms, which could result in

beach closures and declines in recreational shellfish

harvests. Ocean acidification is also expected to negatively

impact important economic species, including oysters and

Pacific salmon.

For more information on climate change impacts on coastal

resources, please visit the Coastal Resources page. |

|

Impacts

on Ecosystems and Agriculture Impacts

on Ecosystems and Agriculture

Higher temperatures, changing streamflows, and increases in

pests and disease threaten forests, agriculture, and fish

populations in the Northwest.

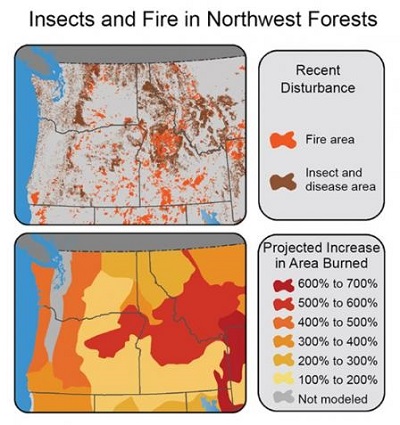

Picture - Under

hotter, drier conditions, insects and fire can have large

cumulative impacts on forests. This is expected to be the

dominant driver of forest change in the near future. The top

map shows areas burned between 1984 and 2008 or affected by

insects or disease between 1997 and 2008. The bottom map

indicates the expected increase in area burned resulting

from a 2.2°F warming in average temperature. Source: USGCRP

2014

Forests make up nearly half of the Northwest landscape.

These areas provide important habitat for fish and wildlife

and support local economies, recreation, and traditional

tribal activities. Forests have become warmer and drier due

to rising temperatures, changes in precipitation, and

reduced soil moisture. These stresses make trees more

susceptible to insect outbreaks and disease and make forests

highly flammable. An increase in the number and size of

wildfires has been observed in the region in recent decades.

These impacts are expected to worsen in the future,

resulting in larger areas burned each year and expanded

spread of pests, including the mountain pine beetle. Some

types of forests and other ecosystems at high elevations are

also expected to disappear from the region by the end of the

century from inability to survive changing climatic

conditions. These changes are likely to have significant

effects on local timber revenues and bioenergy markets.

Commercial fish and shellfish harvested in the Northwest

were valued at $480 million in 2011. Warming waters have

already contributed to earlier migration of sockeye salmon

in some streams and earlier growth of algal blooms in some

lakes. Warmer waters are likely to increase spring and

summer disease and mortality in Chinook and sockeye salmon

in some river basins. Species that spend all or part of

their lives in rivers, including salmon, steelhead, and

trout, will suffer from decreased summer flows and increased

flooding and winter flows. Projections suggest that suitable

habitat for the four trout species in the region will

decline by an average of 47% near the end of this century,

compared to past decades.

Ocean acidification is also expected to negatively impact

shellfish, including oysters, and others species, including

Pacific salmon, resulting in economic and cultural

implications. Warmer coastal waters may alter migratory

patterns and areas of suitable habitat for marine species,

resulting in changes in abundances.

Agriculture is an important economic and cultural component

in rural areas of the Northwest. In the short-term, a longer

growing season and higher levels of atmospheric carbon

dioxide may be beneficial to crops. In the longer-term,

reduced water availability for irrigation, higher

temperatures, and changes in pests, diseases, and weeds may

harm crop yields.

For more information on climate change impacts on forests,

please visit the Forests Impacts page.

For more information on climate change impacts on

agriculture and food supply, please visit the Agriculture

and Food Supply Impacts page. |

|

|

Threatened

Salmon Populations Threatened

Salmon Populations

Human activities already threaten Northwest salmon

populations. These activities include dam building, logging,

pollution, and overfishing. Climate change impacts further

stress these salmon populations. Salmon are particularly

sensitive due to their seasonally timed migration upstream

to breed. Higher winter streamflows and earlier peak

steamflows due to climate change will damage spawning nests,

wash away incubating eggs, and force young salmon from

rivers prematurely. Lower summer streamflows and warmer

stream and ocean temperatures are less favorable for salmon

and other cold-water fish species. These climate change

impacts facilitate the spread of salmon diseases and

parasites. Many salmon species are already considered

threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered

Species Act. Studies show that by 2100, one third of current

habitat for Northwest salmon and other coldwater fish will

be too warm for these species to tolerate.

Picture - Salmon

swimming upstream. Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service |

|

|

EPA Page |

|

This is the

EPA page for this topic. To see if the Trump

administration has changed the EPA page, simply click the

link and compare the information with this page. If you

notice changes were made to the EPA page, please post a

comment. Thanks. |

|

|

Key Points

Warming temperatures and declines in snowpack and streamflow

have been observed in the Northwest in recent decades.

Climate change will likely result in continued reductions in

snowpack and lower summer streamflows, worsening the

existing competition for water.

Higher temperatures, changing streamflows, and an increase

in pests, disease, and wildfire will threaten forests,

agriculture, and salmon populations.

Sea level rise is projected to increase erosion of

coastlines, escalating infrastructure and ecosystem risks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional Climate Change Information |

Climate Change and Carbon Dioxide

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change

and carbon dioxide.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice. |

Carbon Dioxide and Climate Change

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of carbon dioxide

and climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice. |

Environmental Group Warns Earth's Health at Risk

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

A report by the World Wildlife Fund looked at thousands of animal populations

and found they have dropped significantly in 40 years. |

Sea Levels Rising at Fastest Rate in 3,000 years

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

A group of scientists say sea levels are rising at record rates. Another group

found that January temperatures in the Arctic reached a record high. |

Capturing CO2 Gas Is Not Easy

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

Most scientists agree that carbon-dioxide gas is partly to blame for climate

change: rising global temperatures. But capturing the CO2 gas released by power

stations is costly and difficult. |

Growth, Climate Change Threaten African Plants and

Animals

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

Researchers believe Africa may lose as much as 30 percent of its animal and

plant species by the end of this century. |

|

|

|

|

Search Fun Easy English |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About

Contact

Copyright

Resources

Site Map |