|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Climate Change Indicators: Heavy

Precipitation Climate Change Indicators: Heavy

Precipitation

This indicator tracks the frequency of heavy precipitation

events in the United States.

Key Points

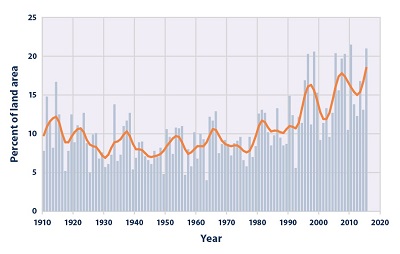

In recent years, a larger percentage of precipitation has

come in the form of intense single-day events. Nine of the

top 10 years for extreme one-day precipitation events have

occurred since 1990 (see Figure 1).

The prevalence of extreme single-day precipitation events

remained fairly steady between 1910 and the 1980s, but has

risen substantially since then. Over the entire period from

1910 to 2015, the portion of the country experiencing

extreme single-day precipitation events increased at a rate

of about half a percentage point per decade (see Figure 1).

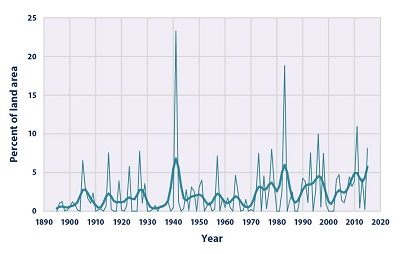

The percentage of land area experiencing much greater than

normal yearly precipitation totals increased between 1895

and 2015. There has been much year-to-year variability,

however. In some years there were no abnormally wet areas,

while a few others had abnormally high precipitation totals

over 10 percent or more of the contiguous 48 states’ land

area (see Figure 2). For example, 1941 was extremely wet in

the West, while 1982 was very wet nationwide.

Figures 1 and 2 are both consistent with other studies that

have found an increase in heavy precipitation over

timeframes ranging from single days to 90-day periods to

whole years. For more information on trends in overall

precipitation levels, see the U.S. and Global Precipitation

indicator. |

|

Background

Heavy precipitation refers to instances during which the

amount of rain or snow experienced in a location

substantially exceeds what is normal. What constitutes a

period of heavy precipitation varies according to location

and season.

Climate change can affect the intensity and frequency of

precipitation. Warmer oceans increase the amount of water

that evaporates into the air. When more moisture-laden air

moves over land or converges into a storm system, it can

produce more intense precipitation—for example, heavier rain

and snow storms.1 The potential impacts of heavy

precipitation include crop damage, soil erosion, and an

increase in flood risk due to heavy rains (see the River

Flooding indicator)—which in turn can lead to injuries,

drownings, and other flooding-related effects on health.2 In

addition, runoff from precipitation can impair water quality

as pollutants deposited on land wash into water bodies.

Heavy precipitation does not necessarily mean the total

amount of precipitation at a location has increased—just

that precipitation is occurring in more intense events.

However, changes in the intensity of precipitation, when

combined with changes in the interval between precipitation

events, can also lead to changes in overall precipitation

totals. |

|

About the Indicator

Heavy precipitation events can be measured by tracking their

frequency, examining their return period (the chance that

the event will be equaled or exceeded in a given year), or

directly measuring the amount of precipitation in a certain

period (for example, inches of rain falling in a 24-hour

period).

One way to track heavy precipitation is by calculating what

percentage of a particular location’s total precipitation in

a given year has come in the form of extreme one-day

events—or, in other words, what percentage of precipitation

is arriving in short, intense bursts. Figure 1 of this

indicator looks at the prevalence of extreme single-day

precipitation events over time.

For added insight, this indicator also tracks the occurrence

of unusually high total yearly precipitation. It does so by

looking at the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), which

compares actual yearly precipitation totals with the range

of precipitation totals that one would typically expect at a

specific location, based on historical data. If a location

experiences less precipitation than normal during a

particular period, it will receive a negative SPI score,

while a period with more precipitation than normal will

receive a positive score. The more precipitation (compared

with normal), the higher the SPI score. The SPI is a useful

way to look at precipitation totals because it allows

comparison of different locations and different seasons on a

standard scale. Figure 2 shows what percentage of the total

area of the contiguous 48 states had an annual SPI score of

2.0 or above (well above normal) in any given year.

Indicator Notes

Weather monitoring stations tend to be closer together in

the eastern and central states than in the western states.

In areas with fewer monitoring stations, heavy precipitation

indicators are less likely to reflect local conditions

accurately.

Data Sources

The data used for this indicator come from a large national

network of weather stations and were provided by the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s)

National Centers for Environmental Information. Figure 1 is

based on Step #4 of NOAA’s U.S. Climate Extremes Index; for

data and a description of the index, see:

www.ncdc.noaa.gov/extremes/cei. Figure 2 is based on the

U.S. SPI, which is shown in a variety of maps available

online at:

www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/drought. The data used to

construct these maps are available at:

ftp://ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/cirs/climdiv/.

Technical Documentation

Download related technical information PDF |

|

Figure

1. Extreme One-Day Precipitation Events in the

Contiguous 48 States, 1910–2015 Figure

1. Extreme One-Day Precipitation Events in the

Contiguous 48 States, 1910–2015

This figure shows the percentage of the land area of the

contiguous 48 states where a much greater than normal

portion of total annual precipitation has come from extreme

single-day precipitation events. The bars represent

individual years, while the line is a nine-year weighted

average.

Data source: NOAA, 20166 |

Figure

2. Unusually High Annual Precipitations in the

Contiguous 48 States, 1895–2015 Figure

2. Unusually High Annual Precipitations in the

Contiguous 48 States, 1895–2015

This figure shows the percentage of the land area of the

contiguous 48 states that experienced much greater than

normal precipitation in any given year, which means it

scored 2.0 or above on the annual Standardized Precipitation

Index. The thicker line shows a nine-year weighted average

that smooths out some of the year-to-year fluctuations.

Data source: NOAA, 20167 |

|

|

|

EPA Page |

|

This is the

EPA page for this topic. To see if the Trump

administration has changed the EPA page, simply click the

link and compare the information with this page. If you

notice changes were made to the EPA page, please post a

comment. Thanks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional Climate Change Information |

Climate Change and Carbon Dioxide

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change

and carbon dioxide.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice. |

Carbon Dioxide and Climate Change

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of carbon dioxide

and climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice. |

Environmental Group Warns Earth's Health at Risk

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

A report by the World Wildlife Fund looked at thousands of animal populations

and found they have dropped significantly in 40 years. |

Sea Levels Rising at Fastest Rate in 3,000 years

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

A group of scientists say sea levels are rising at record rates. Another group

found that January temperatures in the Arctic reached a record high. |

Capturing CO2 Gas Is Not Easy

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

Most scientists agree that carbon-dioxide gas is partly to blame for climate

change: rising global temperatures. But capturing the CO2 gas released by power

stations is costly and difficult. |

Growth, Climate Change Threaten African Plants and

Animals

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

Researchers believe Africa may lose as much as 30 percent of its animal and

plant species by the end of this century. |

|

|

|

|

Search Fun Easy English |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About

Contact

Copyright

Resources

Site Map |