|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Climate Change Indicators: River

Flooding Climate Change Indicators: River

Flooding

This indicator examines changes in the size and frequency of

inland river flood events in the United States.

Key Points

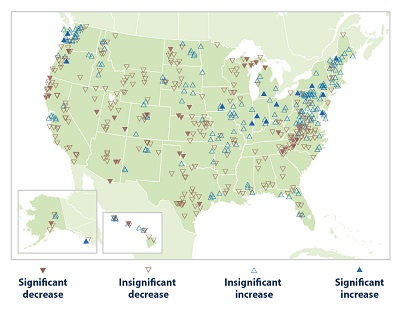

Floods have generally become larger in rivers and streams

across large parts of the Northeast and Midwest. Flood

magnitude has generally decreased in the West, southern

Appalachia, and northern Michigan (see Figure 1).

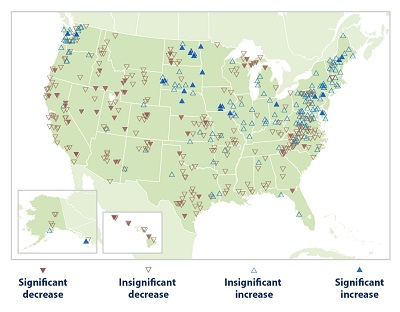

Large floods have become more frequent across the Northeast,

Pacific Northwest, and northern Great Plains. Flood

frequency has decreased in some other parts of the country,

especially the Southwest and the Rockies (see Figure 2).

Increases and decreases in frequency and magnitude of river

flood events generally coincide with increases and decreases

in the frequency of heavy rainfall events. |

|

Background

Rivers and streams experience flooding as a natural result

of large rain storms or spring snowmelt that quickly drains

into streams and rivers. Although the risk for flooding

varies across the United States, most areas are susceptible

to floods, even in dry and mountainous regions. The size, or

magnitude, of flood events is influenced by how much water

enters the waterway upstream—and how quickly. Flood

frequency largely depends on the frequency of weather

events.

Large flood events can damage homes, roads, bridges, and

other infrastructure; wipe out farmers’ crops; and harm or

displace people. Although regular flooding helps to maintain

the nutrient balance of soils in the flood plain, larger or

more frequent floods could disrupt ecosystems by displacing

aquatic life, impairing water quality, and increasing soil

erosion. By inundating water treatment systems with sediment

and contaminants, and promoting the growth of harmful

microbes, floods can directly affect the water supplies that

communities depend on.

Climate change may cause river floods to become larger or

more frequent than they used to be in some places, yet

become smaller and less frequent in other places. As warmer

temperatures cause more water to evaporate from the land and

oceans, changes in the size and frequency of heavy

precipitation events may in turn affect the size and

frequency of river flooding (see the Heavy Precipitation

indicator).1 Changes in streamflow, the timing of snowmelt

(see the Streamflow indicator), and the amount of snowpack

that accumulates in the winter (see the Snowpack indicator)

can also affect flood patterns. |

|

About the Indicator

The U.S. Geological Survey maintains thousands of stream

gauges across the United States. Each gauge measures water

level and discharge—the amount of water flowing past the

gauge. This indicator uses total daily discharge data from

about 500 long-term stream gauge stations where trends are

not substantially influenced by dams, reservoir management,

wastewater treatment facilities, or land-use change.

One way to determine whether the magnitude of flooding has

changed is by studying the largest flood event from each

year. This indicator examines the maximum discharge from

every year at every station to identify whether peak flows

have generally increased or decreased. This indicator also

analyzes whether large flood events have become more or less

frequent over time, based on daily discharge records.

This indicator starts in 1965 because flood data have been

available for a large number of sites to support a

national-level analysis since then.

Indicator Notes

This indicator is based on U.S. stream gauges that have

recorded data consistently since 1965. Besides climate

change, many other types of human influences could affect

the frequency and magnitude of floods—for example, dams,

floodwater management activities, agricultural practices,

and changes in land use. To remove these influences, this

indicator focuses on a set of sites that are not heavily

influenced by human activities, in watersheds that do not

have a large proportion of impervious surfaces such as

concrete and asphalt. Increased flooding does not

necessarily result in an increased risk to people or

property if an area has protective infrastructure, such as

levees or floodwalls.

Data Sources

Daily stream gauge data were collected by the U.S.

Geological Survey. These data came from a set of gauges in

watersheds with minimal human impacts, which have been

classified as reference gauges.6 Daily discharge data are

stored in the National Water Information System and are

publicly available at:

https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis.

Technical Documentation

Download related technical information PDF |

|

Figure

1. Change in the Magnitude of River Flooding in the

United States, 1965–2015 Figure

1. Change in the Magnitude of River Flooding in the

United States, 1965–2015

This figure shows changes in the size of flooding events in

rivers and streams in the United States between 1965 and

2015. Blue upward-pointing symbols show locations where

floods have become larger; brown downward-pointing symbols

show locations where floods have become smaller. The larger,

solid-color symbols represent stations where the change was

statistically significant.

Data source: Slater and Villarini, 20164 |

Figure

2. Change in the Frequency of River Flooding in the

United States, 1965–2015 Figure

2. Change in the Frequency of River Flooding in the

United States, 1965–2015

This figure shows changes in the frequency of flooding

events in rivers and streams in the United States between

1965 and 2015. Blue upward-pointing symbols show locations

where floods have become more frequent; brown

downward-pointing symbols show locations where floods have

become less frequent. The larger, solid-color symbols

represent stations where the change was statistically

significant.

Data source: Slater and Villarini, 20165 |

|

|

|

EPA Page |

|

This is the

EPA page for this topic. To see if the Trump

administration has changed the EPA page, simply click the

link and compare the information with this page. If you

notice changes were made to the EPA page, please post a

comment. Thanks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional Climate Change Information |

Climate Change and Carbon Dioxide

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change

and carbon dioxide.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice. |

Carbon Dioxide and Climate Change

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of carbon dioxide

and climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice. |

Environmental Group Warns Earth's Health at Risk

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

A report by the World Wildlife Fund looked at thousands of animal populations

and found they have dropped significantly in 40 years. |

Sea Levels Rising at Fastest Rate in 3,000 years

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

A group of scientists say sea levels are rising at record rates. Another group

found that January temperatures in the Arctic reached a record high. |

Capturing CO2 Gas Is Not Easy

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

Most scientists agree that carbon-dioxide gas is partly to blame for climate

change: rising global temperatures. But capturing the CO2 gas released by power

stations is costly and difficult. |

Growth, Climate Change Threaten African Plants and

Animals

(Beginner - Listening,

reading)

A video lesson to

help with your understanding of climate change.

The English is

spoken at 75% of normal speed.

Great English listening and reading practice.

Researchers believe Africa may lose as much as 30 percent of its animal and

plant species by the end of this century. |

|

|

|

|

Search Fun Easy English |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About

Contact

Copyright

Resources

Site Map |