|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

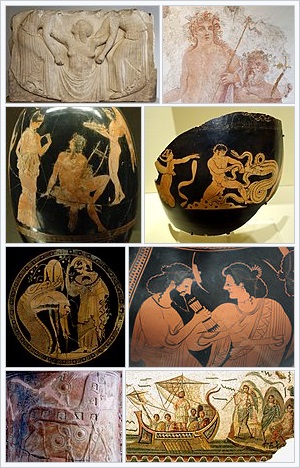

| Scenes from Greek

mythology depicted in ancient art.

Left-to-right, top-to-bottom: the birth of

Aphrodite, a revel with Dionysus and Silenus,

Adonis playing the kithara for Aphrodite,

Heracles slaying the Lernaean Hydra, the

Colchian dragon regurgitating Jason in the

presence of Athena, Hermes with his mother Maia,

the Trojan Horse, and Odysseus's ship sailing

past the island of the sirens. |

Greek

Mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by

the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek

folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of

the world, the lives and activities of deities, heroes,

and mythological creatures, and the origins and

significance of the ancient Greeks' own cult and ritual

practices. Modern scholars study the myths to shed light

on the religious and political institutions of ancient

Greece, and to better understand the nature of

myth-making itself.

The Greek myths were initially propagated in an

oral-poetic tradition most likely by Minoan and

Mycenaean singers starting in the 18th century BC;

eventually the myths of the heroes of the Trojan War and

its aftermath became part of the oral tradition of

Homer's epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Two poems

by Homer's near contemporary Hesiod, the Theogony and

the Works and Days, contain accounts of the genesis of

the world, the succession of divine rulers, the

succession of human ages, the origin of human woes, and

the origin of sacrificial practices. Myths are also

preserved in the Homeric Hymns, in fragments of epic

poems of the Epic Cycle, in lyric poems, in the works of

the tragedians and comedians of the fifth century BC, in

writings of scholars and poets of the Hellenistic Age,

and in texts from the time of the Roman Empire by

writers such as Plutarch and Pausanias. |

|

|

| Zeus, disguised as a

swan, seduces Leda, the Queen of Sparta. A

sixteenth-century copy of the lost original by

Michelangelo. |

Origins of the

world and the gods

"Myths of origin" or "creation myths" represent an

attempt to explain the beginnings of the universe in

human language. The most widely accepted version at the

time, although a philosophical account of the beginning

of things, is reported by Hesiod, in his Theogony. He

begins with Chaos, a yawning nothingness. Out of the

void emerged Gaia (the Earth) and some other primary

divine beings: Eros (Love), the Abyss (the Tartarus),

and the Erebus. Without male assistance, Gaia gave birth

to Uranus (the Sky) who then fertilized her. From that

union were born first the Titans—six males: Coeus, Crius,

Cronus, Hyperion, Iapetus, and Oceanus; and six females:

Mnemosyne, Phoebe, Rhea, Theia, Themis, and Tethys.

After Cronus was born, Gaia and Uranus decreed no more

Titans were to be born. They were followed by the

one-eyed Cyclopes and the Hecatonchires or

Hundred-Handed Ones, who were both thrown into Tartarus

by Uranus. This made Gaia furious. Cronus ("the wily,

youngest and most terrible of Gaia's children"), was

convinced by Gaia to castrate his father. He did this

and became the ruler of the Titans with his sister-wife,

Rhea, as his consort, and the other Titans became his

court.

A motif of father-against-son conflict was repeated when

Cronus was confronted by his son, Zeus. Because Cronus

had betrayed his father, he feared that his offspring

would do the same, and so each time Rhea gave birth, he

snatched up the child and ate it. Rhea hated this and

tricked him by hiding Zeus and wrapping a stone in a

baby's blanket, which Cronus ate. When Zeus was

full-grown, he fed Cronus a drugged drink which caused

him to vomit, throwing up Rhea's other children,

including Poseidon, Hades, Hestia, Demeter, and Hera,

and the stone, which had been sitting in Cronus's

stomach all this time. Zeus then challenged Cronus to

war for the kingship of the gods. At last, with the help

of the Cyclopes (whom Zeus freed from Tartarus), Zeus

and his siblings were victorious, while Cronus and the

Titans were hurled down to imprisonment in Tartarus.

Zeus was plagued by the same concern, and after a

prophecy that the offspring of his first wife, Metis,

would give birth to a god "greater than he", Zeus

swallowed her. She was already pregnant with Athena,

however, and she burst forth from his head—fully-grown

and dressed for war. |

|

|

| El Juicio de Paris

by Enrique Simonet, 1904. Paris is holding the

golden apple on his right hand while surveying

the goddesses in a calculative manner. |

Greek pantheon

According to Classical-era mythology, after the

overthrow of the Titans, the new pantheon of gods and

goddesses was confirmed. Among the principal Greek gods

were the Olympians, residing on Mount Olympus under the

eye of Zeus. (The limitation of their number to twelve

seems to have been a comparatively modern idea.) Besides

the Olympians, the Greeks worshipped various gods of the

countryside, the satyr-god Pan, Nymphs (spirits of

rivers), Naiads (who dwelled in springs), Dryads (who

were spirits of the trees), Nereids (who inhabited the

sea), river gods, Satyrs, and others. In addition, there

were the dark powers of the underworld, such as the

Erinyes (or Furies), said to pursue those guilty of

crimes against blood-relatives. In order to honor the

Ancient Greek pantheon, poets composed the Homeric Hymns

(a group of thirty-three songs). Gregory Nagy (1992)

regards "the larger Homeric Hymns as simple preludes

(compared with Theogony), each of which invokes one

god."

The gods of Greek mythology are described as having

essentially corporeal but ideal bodies. According to

Walter Burkert, the defining characteristic of Greek

anthropomorphism is that "the Greek gods are persons,

not abstractions, ideas or concepts." Regardless of

their underlying forms, the Ancient Greek gods have many

fantastic abilities; most significantly, the gods are

not affected by disease, and can be wounded only under

highly unusual circumstances. The Greeks considered

immortality as the distinctive characteristic of their

gods; this immortality, as well as unfading youth, was

insured by the constant use of nectar and ambrosia, by

which the divine blood was renewed in their veins.

Each god descends from his or her own genealogy, pursues

differing interests, has a certain area of expertise,

and is governed by a unique personality; however, these

descriptions arise from a multiplicity of archaic local

variants, which do not always agree with one another.

When these gods are called upon in poetry, prayer, or

cult, they are referred to by a combination of their

name and epithets, that identify them by these

distinctions from other manifestations of themselves

(e.g., Apollo Musagetes is "Apollo, [as] leader of the

Muses"). Alternatively, the epithet may identify a

particular and localized aspect of the god, sometimes

thought to be already ancient during the classical epoch

of Greece.

Most gods were associated with specific aspects of life.

For example, Aphrodite was the goddess of love and

beauty, Ares was the god of war, Hades the ruler of the

underworld, and Athena the goddess of wisdom and

courage. Some gods, such as Apollo and Dionysus,

revealed complex personalities and mixtures of

functions, while others, such as Hestia (literally

"hearth") and Helios (literally "sun"), were little more

than personifications. The most impressive temples

tended to be dedicated to a limited number of gods, who

were the focus of large pan-Hellenic cults. It was,

however, common for individual regions and villages to

devote their own cults to minor gods. Many cities also

honored the more well-known gods with unusual local

rites and associated strange myths with them that were

unknown elsewhere. During the heroic age, the cult of

heroes (or demigods) supplemented that of the gods. |

|

|

| Botticelli's The

Birth of Venus (c.1485–1486, oil on canvas,

Uffizi, Florence)—a revived Venus Pudica for a

new view of pagan Antiquity—is often said to

epitomize for modern viewers the spirit of the

Renaissance. |

Trojan War and

aftermath

Greek mythology culminates in the Trojan War, fought

between Greece and Troy, and its aftermath. In Homer's

works, such as the Iliad, the chief stories have already

taken shape and substance, and individual themes were

elaborated later, especially in Greek drama. The Trojan

War also elicited great interest in the Roman culture

because of the story of Aeneas, a Trojan hero whose

journey from Troy led to the founding of the city that

would one day become Rome, as recounted in Virgil's

Aeneid (Book II of Virgil's Aeneid contains the

best-known account of the sack of Troy). Finally there

are two pseudo-chronicles written in Latin that passed

under the names of Dictys Cretensis and Dares Phrygius.

The Trojan War cycle, a collection of epic poems, starts

with the events leading up to the war: Eris and the

golden apple of Kallisti, the Judgement of Paris, the

abduction of Helen, the sacrifice of Iphigenia at Aulis.

To recover Helen, the Greeks launched a great expedition

under the overall command of Menelaus's brother,

Agamemnon, king of Argos, or Mycenae, but the Trojans

refused to return Helen. The Iliad, which is set in the

tenth year of the war, tells of the quarrel between

Agamemnon and Achilles, who was the finest Greek

warrior, and the consequent deaths in battle of

Achilles' beloved comrade Patroclus and Priam's eldest

son, Hector. After Hector's death the Trojans were

joined by two exotic allies, Penthesilea, queen of the

Amazons, and Memnon, king of the Ethiopians and son of

the dawn-goddess Eos. Achilles killed both of these, but

Paris then managed to kill Achilles with an arrow in the

heel. Achilles' heel was the only part of his body which

was not invulnerable to damage by human weaponry. Before

they could take Troy, the Greeks had to steal from the

citadel the wooden image of Pallas Athena (the

Palladium). Finally, with Athena's help, they built the

Trojan Horse. Despite the warnings of Priam's daughter

Cassandra, the Trojans were persuaded by Sinon, a Greek

who feigned desertion, to take the horse inside the

walls of Troy as an offering to Athena; the priest

Laocoon, who tried to have the horse destroyed, was

killed by sea-serpents. At night the Greek fleet

returned, and the Greeks from the horse opened the gates

of Troy. In the total sack that followed, Priam and his

remaining sons were slaughtered; the Trojan women passed

into slavery in various cities of Greece. The

adventurous homeward voyages of the Greek leaders

(including the wanderings of Odysseus and Aeneas (the

Aeneid), and the murder of Agamemnon) were told in two

epics, the Returns (the lost Nostoi) and Homer's

Odyssey. The Trojan cycle also includes the adventures

of the children of the Trojan generation (e.g., Orestes

and Telemachus). |

|

|

Greek Mythological Creatures

A host of legendary creatures, animals, and mythic

humanoids occur in ancient Greek mythology. Click the

following Wikipedia link for a really long list of very

cool creatures.

Wikipedia: List of Greek mythological creatures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Fun Easy English |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About

Contact

Copyright

Resources

Site Map |