|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

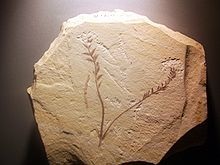

| Facsimile of a

fossil of Archaefructus from the Yixian

Formation, China. |

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( /krɪˈteɪ.ʃəs/, krih-TAY-shəs) is a

geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66

million years ago (mya). It is the third and final

period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At

nearly 80 million years, it is the longest geological

period of the entire Phanerozoic. The name is derived

from the Latin creta, 'chalk', which is abundant in the

latter half of the period. It is usually abbreviated K,

for its German translation Kreide.

The Cretaceous was a period with a relatively warm

climate, resulting in high eustatic sea levels that

created numerous shallow inland seas. These oceans and

seas were populated with now-extinct marine reptiles,

ammonites and rudists, while dinosaurs continued to

dominate on land. The world was ice free, and forests

extended to the poles. During this time, new groups of

mammals and birds appeared. During the Early Cretaceous,

flowering plants appeared and began to rapidly

diversify, becoming the dominant group of plants across

the Earth by the end of the Cretaceous, coincident with

the decline and extinction of previously widespread

gymnosperm groups.

The Cretaceous (along with the Mesozoic) ended with the

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, a large mass

extinction in which many groups, including non-avian

dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and large marine reptiles died

out. The end of the Cretaceous is defined by the abrupt

Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–Pg boundary), a

geologic signature associated with the mass extinction

which lies between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras.

Etymology and history

The Cretaceous as a separate period was first defined by

Belgian geologist Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in 1822 as the

"Terrain Crétacé", using strata in the Paris Basin and

named for the extensive beds of chalk (calcium carbonate

deposited by the shells of marine invertebrates,

principally coccoliths), found in the upper Cretaceous

of Western Europe. The name Cretaceous was derived from

Latin creta, meaning chalk. The twofold division of the

Cretaceous was implemented by Conybeare and Phillips in

1822. Alcide d'Orbigny in 1840 divided the French

Cretaceous into 5 “étages” (stages): the Neocomian,

Aptian, Albian, Turonian and Senonian, later adding the

"Urgonian" between Neocomian and Aptian and the

Cenomanian between the Albian and Turonian. |

|

|

| The impact of a

meteorite or comet is today widely accepted as

the main reason for the Cretaceous–Paleogene

extinction event. |

Geology

Boundaries

The impact of a meteorite or comet is today widely

accepted as the main reason for the Cretaceous–Paleogene

extinction event.

There is not yet a globally-defined lower stratigraphic

boundary representing the start of the period. However,

the top of the system is sharply defined, being placed

at an iridium-rich layer found worldwide that is

believed to be associated with the Chicxulub impact

crater, with its boundaries circumscribing parts of the

Yucatán Peninsula and into the Gulf of Mexico. This

layer has been dated at 66.043 Ma.

A 140 Ma age for the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary

instead of the usually accepted 145 Ma was proposed in

2014 based on a stratigraphic study of Vaca Muerta

Formation in Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Víctor Ramos, one

of the authors of the study proposing the 140 Ma

boundary age, sees the study as a "first step" toward

formally changing the age in the International Union of

Geological Sciences.

At the end of the Cretaceous, the impact of a large body

with the Earth may have been the punctuation mark at the

end of a progressive decline in biodiversity during the

Maastrichtian Age. The result was the extinction of

three-quarters of Earth's plant and animal species. The

impact created the sharp break known as K–Pg boundary

(formerly known as the K–T boundary). Earth's

biodiversity required substantial time to recover from

this event, despite the probable existence of an

abundance of vacant ecological niches. |

|

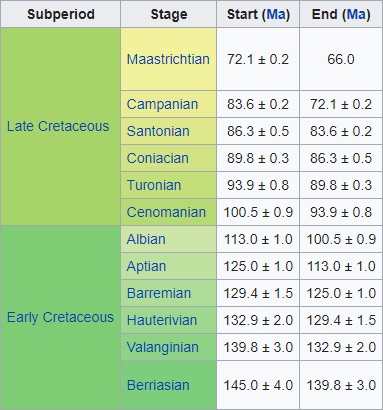

| Subperiods and

stages of the Cretaceous. |

Stratigraphy

The Cretaceous is divided into Early and Late Cretaceous

epochs, or Lower and Upper Cretaceous series. In older

literature the Cretaceous is sometimes divided into

three series: Neocomian (lower/early), Gallic (middle)

and Senonian (upper/late). A subdivision in twelve

stages, all originating from European stratigraphy, is

now used worldwide. In many parts of the world,

alternative local subdivisions are still in use.

From youngest to oldest, the subdivisions of the

Cretaceous period areas shown in the graphic.

Geologic formations

The high sea level and warm climate of the Cretaceous

meant large areas of the continents were covered by

warm, shallow seas, providing habitat for many marine

organisms. The Cretaceous was named for the extensive

chalk deposits of this age in Europe, but in many parts

of the world, the deposits from the Cretaceous are of

marine limestone, a rock type that is formed under warm,

shallow marine conditions. Due to the high sea level,

there was extensive space for such sedimentation.

Because of the relatively young age and great thickness

of the system, Cretaceous rocks are evident in many

areas worldwide.

Chalk is a rock type characteristic for (but not

restricted to) the Cretaceous. It consists of coccoliths,

microscopically small calcite skeletons of

coccolithophores, a type of algae that prospered in the

Cretaceous seas.

Stagnation of deep sea currents in middle Cretaceous

times caused anoxic conditions in the sea water leaving

the deposited organic matter undecomposed. Half of the

world's petroleum reserves were laid down at this time

in the anoxic conditions of what would become the

Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mexico. In many places

around the world, dark anoxic shales were formed during

this interval, such as the Mancos Shale of western North

America. These shales are an important source rock for

oil and gas, for example in the subsurface of the North

Sea. |

|

|

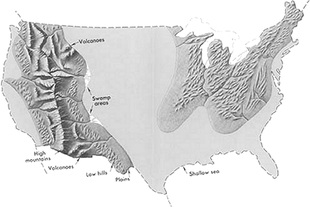

| Map of North America

during the mid-Cretaceous (95 mya), showing

Laramidia (left), Appalachia (right), the

Western Interior Seaway (center and upper left),

and other nearby seaways. |

Paleogeography

During the Cretaceous, the

late-Paleozoic-to-early-Mesozoic supercontinent of

Pangaea completed its tectonic breakup into the

present-day continents, although their positions were

substantially different at the time. As the Atlantic

Ocean widened, the convergent-margin mountain building (orogenies)

that had begun during the Jurassic continued in the

North American Cordillera, as the Nevadan orogeny was

followed by the Sevier and Laramide orogenies.

Gondwana had begun to break up during the Jurassic

period, but its fragmentation accelerated during the

Cretaceous and was largely complete by the end of the

period. South America, Antarctica and Australia rifted

away from Africa (though India and Madagascar remained

attached to each other until around 80 million years

ago); thus, the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans were

newly formed. Such active rifting lifted great undersea

mountain chains along the welts, raising eustatic sea

levels worldwide. To the north of Africa the Tethys Sea

continued to narrow. During the most of the Late

Cretaceous, North America would be divided in two by the

Western Interior Seaway, a large interior sea,

separating Laramidia to the west and Appalachia to the

east, then receded late in the period, leaving thick

marine deposits sandwiched between coal beds. At the

peak of the Cretaceous transgression, one-third of

Earth's present land area was submerged.

The Cretaceous is justly famous for its chalk; indeed,

more chalk formed in the Cretaceous than in any other

period in the Phanerozoic. Mid-ocean ridge activity—or

rather, the circulation of seawater through the enlarged

ridges—enriched the oceans in calcium; this made the

oceans more saturated, as well as increased the

bioavailability of the element for calcareous

nanoplankton. These widespread carbonates and other

sedimentary deposits make the Cretaceous rock record

especially fine. Famous formations from North America

include the rich marine fossils of Kansas's Smoky Hill

Chalk Member and the terrestrial fauna of the late

Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation. Other important

Cretaceous exposures occur in Europe (e.g., the Weald)

and China (the Yixian Formation). In the area that is

now India, massive lava beds called the Deccan Traps

were erupted in the very late Cretaceous and early

Paleocene. |

|

| Geography of the

Contiguous United States in the Late Cretaceous

period. |

Climate

The cooling trend of the last epoch of the Jurassic

continued into the first age of the Cretaceous. There is

evidence that snowfalls were common in the higher

latitudes, and the tropics became wetter than during the

Triassic and Jurassic. Glaciation was however restricted

to high-latitude mountains, though seasonal snow may

have existed farther from the poles. Rafting by ice of

stones into marine environments occurred during much of

the Cretaceous, but evidence of deposition directly from

glaciers is limited to the Early Cretaceous of the

Eromanga Basin in southern Australia.

After the end of the first age, however, temperatures

increased again, and these conditions were almost

constant until the end of the period. The warming may

have been due to intense volcanic activity which

produced large quantities of carbon dioxide. Between 70

and 69 Ma and 66–65 Ma, isotopic ratios indicate

elevated atmospheric CO2 pressures with levels of

1000–1400 ppmV and mean annual temperatures in west

Texas between 21 and 23 °C (70 and 73 °F). Atmospheric

CO2 and temperature relations indicate a doubling of

pCO2 was accompanied by a ~0.6 °C increase in

temperature. The production of large quantities of

magma, variously attributed to mantle plumes or to

extensional tectonics, further pushed sea levels up, so

that large areas of the continental crust were covered

with shallow seas. The Tethys Sea connecting the

tropical oceans east to west also helped to warm the

global climate. Warm-adapted plant fossils are known

from localities as far north as Alaska and Greenland,

while dinosaur fossils have been found within 15 degrees

of the Cretaceous south pole. It was suggest that there

was Antarctic marine glaciation in the Turonian Age,

based on isotopic evidence. However, this has

subsequently been suggest to be the result of

inconsistent isotopic proxies, with evidence of polar

rainforests during this time interval at 82° S.

A very gentle temperature gradient from the equator to

the poles meant weaker global winds, which drive the

ocean currents, resulted in less upwelling and more

stagnant oceans than today. This is evidenced by

widespread black shale deposition and frequent anoxic

events. Sediment cores show that tropical sea surface

temperatures may have briefly been as warm as 42 °C (108

°F), 17 °C (31 °F) warmer than at present, and that they

averaged around 37 °C (99 °F). Meanwhile, deep ocean

temperatures were as much as 15 to 20 °C (27 to 36 °F)

warmer than today's. |

|

Flora

Flowering plants (angiosperms) make up around 90% of

living plant species today. Prior to the rise of

angiosperms, during the Jurassic and the Early

Cretaceous, the higher flora was dominated by gymnosperm

groups, including cycads, conifers, ginkgophytes,

gnetophytes and close relatives, as well as the extinct

Bennettitales. Other groups of plants included

pteridosperms or "seed ferns", a collective term to

refer to disparate groups of fern-like plants that

produce seeds, including groups such as

Corystospermaceae and Caytoniales. The exact origins of

angiosperms are uncertain, with competing hypotheses

including the anthophyte hypothesis, assuming flowering

plants to be closely related to gynetophytes and

Bennettitales as well as the more obscure

Erdtmanithecales. Benettitales, Erdtmanithecales, and

gnetophytes are connected by shared morphological

characters in their seed coats.

Terrestrial fauna

On land, mammals were generally small sized, but a very

relevant component of the fauna, with cimolodont

multituberculates outnumbering dinosaurs in some sites.

Neither true marsupials nor placentals existed until the

very end, but a variety of non-marsupial metatherians

and non-placental eutherians had already begun to

diversify greatly, ranging as carnivores (Deltatheroida),

aquatic foragers (Stagodontidae) and herbivores (Schowalteria,

Zhelestidae). Various "archaic" groups like

eutriconodonts were common in the Early Cretaceous, but

by the Late Cretaceous northern mammalian faunas were

dominated by multituberculates and therians, with

dryolestoids dominating South America.

The apex predators were archosaurian reptiles,

especially dinosaurs, which were at their most diverse

stage. Pterosaurs were common in the early and middle

Cretaceous, but as the Cretaceous proceeded they

declined for poorly understood reasons (once thought to

be due to competition with early birds, but now it is

understood avian adaptive radiation is not consistent

with pterosaur decline), and by the end of the period

only two highly specialized families remained.

Marine fauna

In the seas, rays, modern sharks and teleosts became

common. Marine reptiles included ichthyosaurs in the

early and mid-Cretaceous (becoming extinct during the

late Cretaceous Cenomanian-Turonian anoxic event),

plesiosaurs throughout the entire period, and mosasaurs

appearing in the Late Cretaceous.

Baculites, an ammonite genus with a straight shell,

flourished in the seas along with reef-building rudist

clams. The Hesperornithiformes were flightless, marine

diving birds that swam like grebes. Globotruncanid

Foraminifera and echinoderms such as sea urchins and

starfish (sea stars) thrived. The first radiation of the

diatoms (generally siliceous shelled, rather than

calcareous) in the oceans occurred during the

Cretaceous; freshwater diatoms did not appear until the

Miocene. The Cretaceous was also an important interval

in the evolution of bioerosion, the production of

borings and scrapings in rocks, hardgrounds and shells. |

|

|

Kiddle: Cretaceous Kiddle: Cretaceous

Wikipedia: Cretaceous |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Fun Easy English |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About

Contact

Copyright

Resources

Site Map |