|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

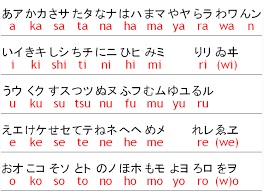

| Table showing the

Japanese basic sounds written in hiragana,

katakana, and romaji. |

Romaji

The romanization of Japanese is the use of Latin script

to write the Japanese language. This method of writing

is sometimes referred to in Japanese as rōmaji (ローマ字,

literally, "Roman letters"; [ɾoːma(d)ʑi] (About this

soundlisten) or [ɾoːmaꜜ(d)ʑi]). There are several

different romanization systems. The three main ones are

Hepburn romanization, Kunrei-shiki romanization (ISO

3602), and Nihon-shiki romanization (ISO 3602 Strict).

Variants of the Hepburn system are the most widely used. |

|

|

Japanese is normally written in a combination of

logographic characters borrowed from Chinese (kanji) and

syllabic scripts (kana) that also ultimately derive from

Chinese characters. Rōmaji may be used in any context

where Japanese text is targeted at non-Japanese speakers

who cannot read kanji or kana, such as for names on

street signs and passports, and in dictionaries and

textbooks for foreign learners of the language. It is

also used to transliterate Japanese terms in text

written in English (or other languages that use the

Latin script) on topics related to Japan, such as

linguistics, literature, history, and culture. Rōmaji is

the most common way to input Japanese into word

processors and computers, and may also be used to

display Japanese on devices that do not support the

display of Japanese characters. |

|

|

All Japanese who have attended elementary school since

World War II have been taught to read and write

romanized Japanese. Therefore, almost all Japanese are

able to read and write Japanese using rōmaji, although

it is extremely rare in Japan to use this method to

write Japanese (except as an input tool on a computer or

for special purposes like in some logo design), and most

Japanese are more comfortable reading kanji and kana. |

|

History

The earliest Japanese romanization system was based on

Portuguese orthography. It was developed around 1548 by

a Japanese Catholic named Anjirō.[citation needed]

Jesuit priests used the system in a series of printed

Catholic books so that missionaries could preach and

teach their converts without learning to read Japanese

orthography. The most useful of these books for the

study of early modern Japanese pronunciation and early

attempts at romanization was the Nippo jisho, a

Japanese–Portuguese dictionary written in 1603. In

general, the early Portuguese system was similar to

Nihon-shiki in its treatment of vowels. Some consonants

were transliterated differently: for instance, the /k/

consonant was rendered, depending on context, as either

c or q, and the /ɸ/ consonant (now pronounced /h/,

except before u) as f; and so Nihon no kotoba ("The

language of Japan") was spelled Nifon no cotoba. The

Jesuits also printed some secular books in romanized

Japanese, including the first printed edition of the

Japanese classic The Tale of the Heike, romanized as

Feiqe no monogatari, and a collection of Aesop's Fables

(romanized as Esopo no fabulas). The latter continued to

be printed and read after the suppression of

Christianity in Japan (Chibbett, 1977).

Following the expulsion of Christians from Japan in the

late 1590s and early 17th century, rōmaji fell out of

use and was used sporadically in foreign texts until the

mid-19th century, when Japan opened up again.

From the mid-19th century onward, several systems were

developed, culminating in the Hepburn system, named

after James Curtis Hepburn who used it in the third

edition of his Japanese–English dictionary, published in

1887. The Hepburn system included representation of some

sounds that have since changed. For example, Lafcadio

Hearn's book Kwaidan shows the older kw- pronunciation;

in modern Hepburn romanization, this would be written

Kaidan (lit. 'ghost tales'). |

|

|

Kiddle: Romanization of Japanese Kiddle: Romanization of Japanese

Wikipedia: Romanization of Japanese |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Fun Easy English |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About

Contact

Copyright

Resources

Site Map |